We Dwell in Possibility is a queer gardening simulation designed by Robert Yang, a videogame developer whose work explores gay subcultures and intimacy, with visuals by cartoonist and illustrator Eleanor Davis.

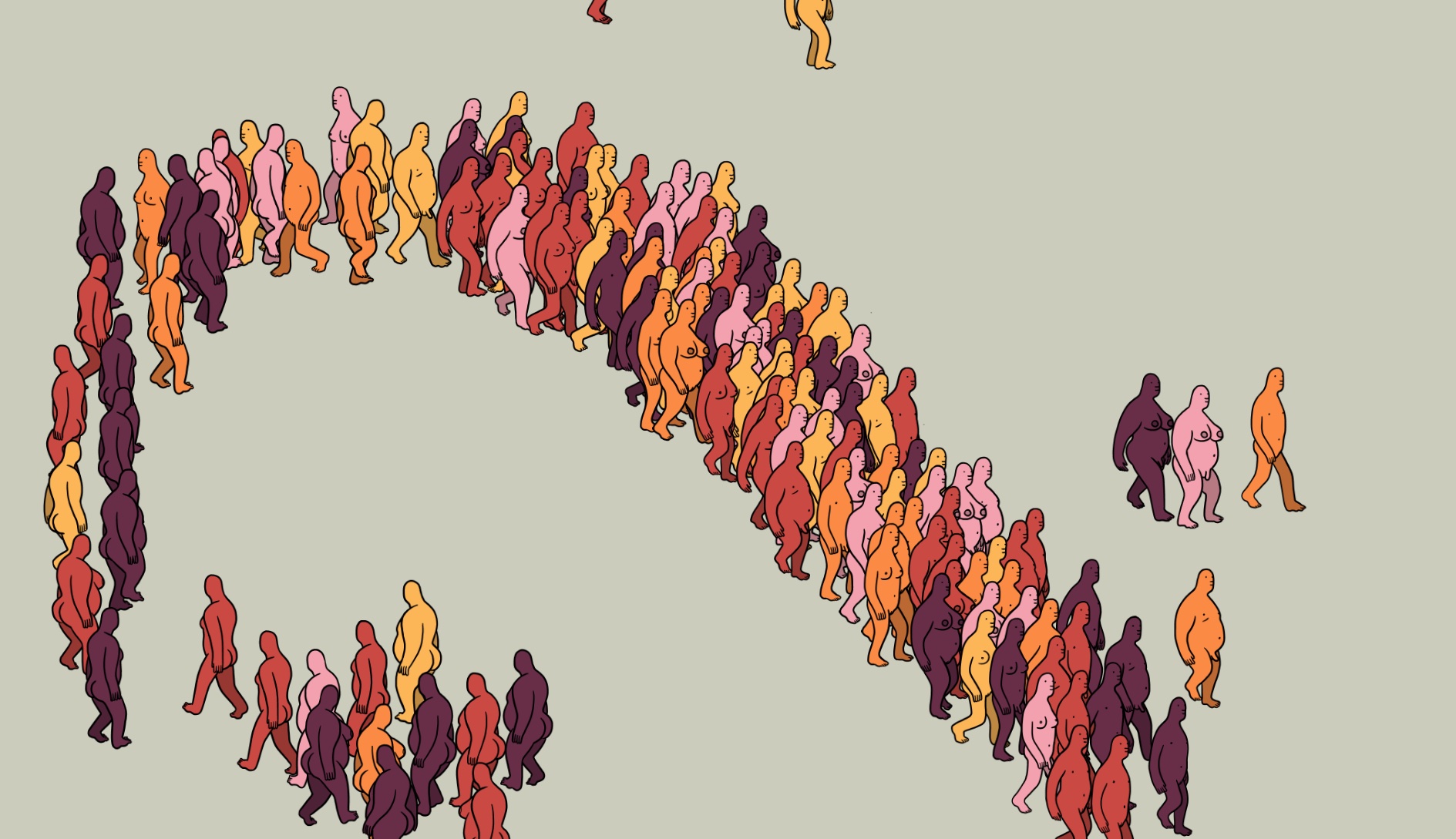

Subverting crowd simulations used by architects of physical buildings, We Dwell in Possibility invites the player to create their own improvised landscape. A virtual heaven or hell, or maybe both at once – a society. After planting bodies and ideas, players can watch them grow while AI ‘peeps’ move across the screen.

Best experienced landscape.

About

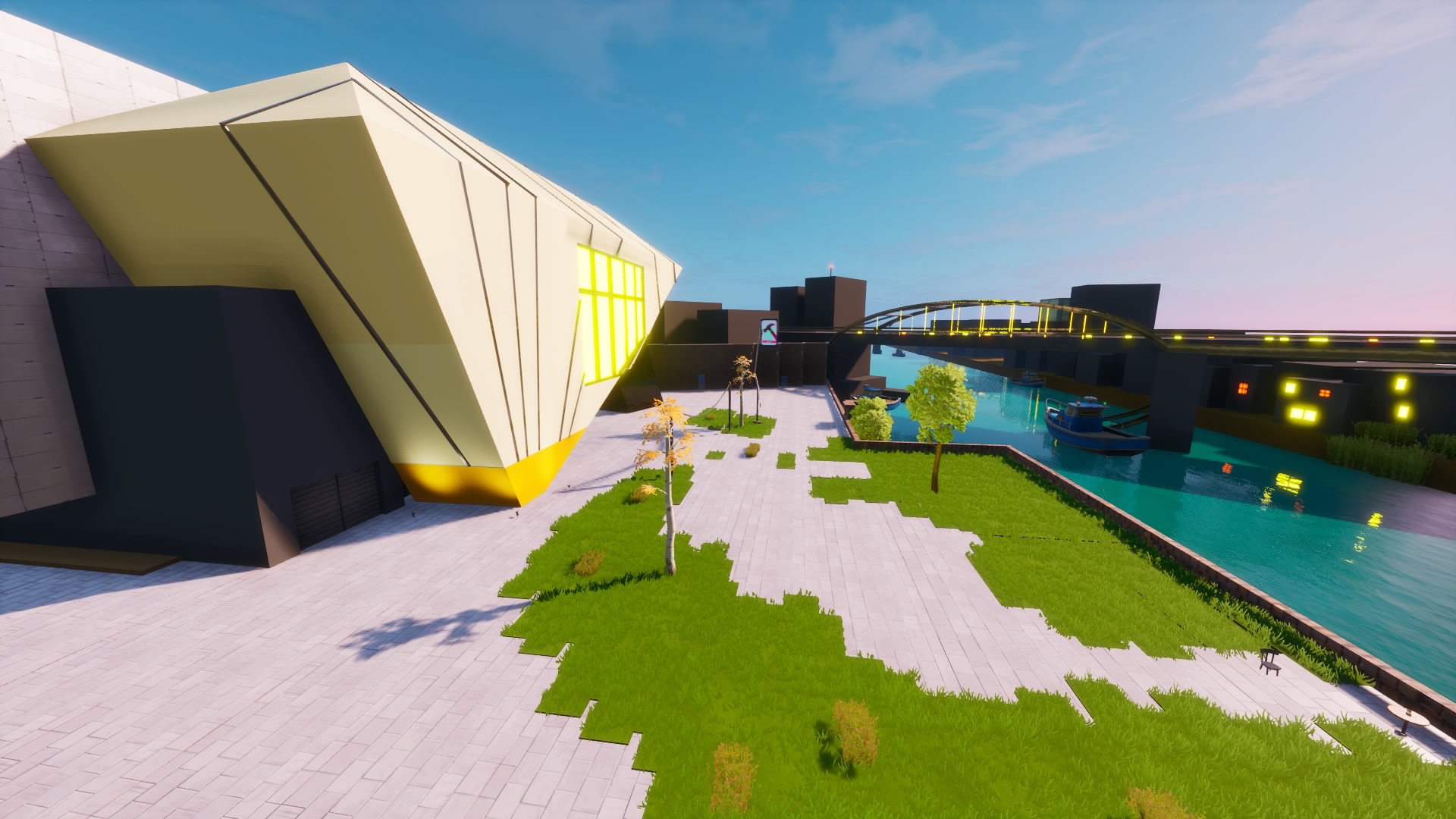

Virtual Factory is a major series of online artworks inspired by the architecture and the ambition of Aviva Studios, the home of Factory International.

We’ve invited some of the world’s most exciting artists to make online works that throw open the doors of our future home before they’ve been built – laying the foundations for what will be possible at Aviva Studios.

The four artists will reimagine our world and construct new worlds of their own, reclaiming the virtual environment as a space for infinite possibility. The programme features new work from:

LaTurbo Avedon is an artist and avatar that shapeshifts through the digital realm and multiplayer games such as Second Life and Final Fantasy. Your Progress Will Be Saved, which launched Virtual Factory, premiered in summer 2020.

Tai Shani is a Turner Prize-winning visual artist who crafts dark, fantastical worlds drawing on forgotten histories – including The Neon Hieroglyph, the second Virtual Factory event, which premiered in March 2021.

Robert Yang is an artist, writer and game designer who has created a series of acclaimed videogames on gay culture and intimacy, and who premiered We Dwell in Possibility, his Virtual Factory work created in collaboration with Eleanor Davis, in July 2021.

Jenn Nkiru is known for her powerful films on Blackness and Black identity and her new work will complete the Virtual Factory series in 2023.

As videogame creators develop ever more compelling and complex online universes, it’s impossible to ignore their influence on our world. Virtual Factory explores how artists are responding to this cultural shift, pushing us to consider how virtual architecture can become an extension of our bodies and minds.

Follow the journey on social media by using the hashtag #VirtualFactory.

About Aviva Studios

Aviva Studios is a new world-class cultural space now open in Manchester, UK. Inspired by our city’s unmatched history of innovation, it will be the year-round home of Manchester International Festival – a space for the world’s greatest artists and thinkers to make, explore and experiment, and for communities and individuals from Manchester and beyond to meet, exchange ideas and learn new skills.

Aviva Studios is designed by Rem Koolhaas’s OMA, with Ellen van Loon as Lead Architect, and backed by Manchester City Council, HM Government and Arts Council England. You can discover more about Aviva Studios here.

Previous Projects

In April 2021, Turner Prize winning-artist Tai Shani took us beyond the merely mortal and into the mystic with The Neon Hieroglyph, her first online artwork.

'The building of a house we will never live in – a house for our ghosts where the gothic and the hallucinatory collide.'

Tai Shani creates worlds that are at once dark yet luminous, both feminist and fantastical – and in The Neon Hieroglyph, she constructed a story-world that draws inspiration from her research into ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and other grains from which LSD is derived, as a psychedelic catalyst.

Ergot played an important part in the North West’s agricultural, social and medical history: linked to local crops and breads, outbreaks of ergot poisoning caused mass hallucinations, with the last reported UK incident during the late 1920s in Manchester. The Neon Hieroglyph used these experiences to spark new visions and alternative realities: a dreamlike CGI journey that takes us from the cellular to the galactic, from the forests to the subterranean, from the real to the almost unimaginable.

Composed of nine short episodes and featuring a mesmeric soundtrack by Manchester-born composer-musician Maxwell Sterling, The Neon Hieroglyph anticipates the kind of extraordinary new art that will be created, produced and presented at Aviva Studios in the coming years.

Robert Yang & Eleanor Davis

We Dwell in Possibility is a queer gardening simulation shaped by intimacy and politics – designed by Robert Yang, a videogame developer whose work explores gay subcultures, with visuals by cartoonist and illustrator Eleanor Davis.

Robert Yang is an architect of virtual space whose work addresses the politics of videogame worlds, asking: who do these worlds represent and who do they exclude? Subverting crowd simulation software used by architects of physical buildings, We Dwell in Possibility invites the player to create their own improvised landscape. A virtual heaven or hell, or maybe both at once – a society.

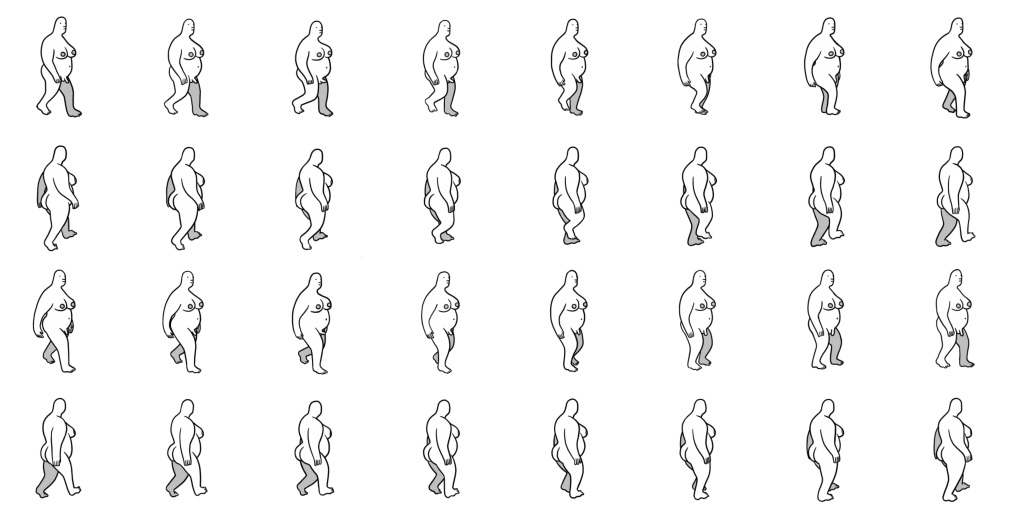

Simulated AI people – ‘peeps’, as Yang calls them – move around naked, alone or in crowds. The seedlings they plant grow into suggestive ‘trees’ that periodically bear fruit – and it’s then for the peeps to decide whether to eat the fruit and transform themselves, or to destroy what they’ve just created.

Free to play, We Dwell in Possibility is the latest new world anticipating the kind of work that will soon be created, produced and presented at Aviva Studios.

About the artists

Robert Yang

Robert Yang makes surprisingly popular games about gay culture and intimacy. He is most known for his historical bathroom sex simulator The Tearoom and his homoerotic shower sim Rinse and Repeat, and his gay sex triptych Radiator 2 has over 150,000 users on Steam. He was previously an Assistant Arts Professor at NYU Game Center. He holds a BA in English Literature from the University of California, Berkeley, and an MFA in Design and Technology from Parsons School of Design.

Eleanor Davis

Eleanor Davis is a cartoonist and illustrator whose books include How To Be Happy, You and a Bike and a Road and Why Art?. Her latest graphic novel, The Hard Tomorrow, won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Graphic Novels & Comics. She lives in Athens, Georgia (pre-COVID) and Tucson, Arizona (mid-COVID).

Credits

- Design by Robert Yang & Eleanor Davis

- Visuals by Eleanor Davis with assistance from Sophia Foster-Dimino

- Code by Robert Yang

- Music by aya

- Sound design by aya & Andy Grier

- Thanks to Drew Weing, Eddie Cameron and the HaxeFlixel community

Commissioned and produced by Factory International.

LaTurbo Avedon

The first Virtual Factory project, Your Progress Will Be Saved, is an online experience created by avatar artist LaTurbo Avedon that reimagines Aviva Studios within Fortnite Creative.

Your Progress Will Be Saved is a journey through LaTurbo Avedon’s world – an adventure down a rabbit hole that leads ever-further away from reality, into depths that probe our relationship with multiuser spaces. Starting from a familiar-looking apartment, you’ll soon escape into the more alluring online wonderlands of music, entertainment and social connection within a vast, virtual architecture. Some will find solace here – but others will look deeper, searching for the seams that hold the illusion together. Your progress will be further rewarded if you find your way out…

Your Progress Will Be Saved has been made within Fortnite Creative, a sandbox game developed and published by Epic Games. It’s part of the hugely popular video game Fortnite, which is spearheading a new generation of online multiplayer games that combine socialising, live events and user-generated spaces.

Experience Your Progress Will Be Saved here.

About the artist

LaTurbo Avedon is an avatar and artist that exists solely online, creating work that emphasises the practice of non-physical identity and authorship. Avedon has spent the past decade developing a body of work that illuminates the ever-growing intensity between users and virtual experiences, pursuing creative environments that deepen the meaning of memories found in cyberspace.

Credits

- LaTurbo Avedon - Artist

- LaTurbo Avedon and Team Cre8 - Design and Gameplay

Events

Contact

For the latest news on Virtual Factory and Factory International’s digital projects, sign-up to our mailing list here. It’s free and we won’t pass your details to anyone else.

Press

For all press enquiries, please contact press@factoryinternational.org.

Connect with us

Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Access

We want as many people as possible to enjoy Virtual Factory, which we’ve developed with accessibility in mind. This website has been tested by individuals with visual, auditory and learning disabilities and their recommendations have been incorporated where possible, though we recognise that the site will not be fully accessible for everyone.

We Dwell In Possibility can also be found on Itch.io

To play the game, click and drag on the figures and objects using your mouse or mouse keys, or just sit back and watch.

• This game is a ‘sandbox’ format, which means that there is no complicated set of instructions – you can explore at your own pace, try things out and see what happens.

• You can also choose to take no action and simply watch what plays out on screen.

• If you pause the game at any time, the instructions above will be there for you to see as a reminder.

• Major visual events in the game are supported by corresponding sound events.

• This game has a conventional control scheme, and you can use your mouse keys as an alternative to a mouse if you prefer.

• You can choose to play the game at a slower speed if you prefer. To adjust this, click the question mark (?) symbol in the top left corner of the screen and select ‘sim speed’. This will switch the game to the slower speed setting.

• You can also choose to mute the soundtrack if you would prefer to play in silence. To mute, click the question mark (?) symbol in the top left corner of the screen and select ‘Sound:On’. This will change to ‘Sound:Muted’.

• Older mobile devices may experience poor sound quality; in this case, we advise muting the game (as above) or trying on another device.

• You can pause the game at any time by clicking the question mark (?) symbol in the top left corner of the screen.

• You can adjust the brightness of the game display choosing either ‘High Contrast’, ‘Dimmed’ or ‘Default’. To do this, click on the question mark (?) in the top left corner and select Screen:Default. This will cycle through to dimmed if pressed once or high contrast if pressed twice.

Device Compatibility

lorem

Notes and Inspiration

By Robert Yang

We Dwell in Possibility is a queer gardening simulation game about planting bodies and ideas, and watching them grow into a kinetic landscape. It was made over several months in collaboration with illustrator Eleanor Davis and musician aya.

Some people may be familiar with my past work: uncanny CG beefcake sex games that toy with hardcore gamer aesthetics, which only run on laptop/desktop computers. For the longest time, I've wanted to make a gay mobile game, but I was unsure how to get my queer politics past Apple and Google's anti-sexuality censors. Browser games celebrate the open internet that exists beyond Silicon Valley's sterilised closed garden. However, the photorealistic 3D graphics of my past games are too heavy and slow for a mobile browser, so I need to make a 2D game even though I've neglected my 2D visual skills. Fortunately, MIF's support has made my collaboration with world-famous illustrator Eleanor Davis not only possible but enjoyable.

Does this game represent a shift or break from my existing work? Maybe. Eleanor's lush visual style is certainly more beautiful than any of my uncanny CG hunks. But formally, I still try to simplify my game interfaces (how to play: drag objects around or do nothing) and embrace a short run time (each simulation loop is about 10 minutes) because I'm still interested in non-traditional audiences. And like my previous games, this project is still very much about bodies, politics and sex. Maybe this project represents a 'virtualisation' of those concerns. Players essentially role-play as gods looking down over their garden, passive or active at their own whim. It's a zoomed-out perspective; it's not immersive, it's a simulation.

And in this simulation, the player sculpts an invisible landscape. Naked simulated AI people ('peeps') arrive and flow across the terrain. Peeps bring objects to plant in the garden, like trees, coffee shops, statues, colossal buttplugs and other necessities. There are dozens of different possible plantings, which can make peeps happy, angry, horny or even Tories. From this simple model of politics, sexuality, and landscape architecture, the player improvises a virtual heaven or hell, or more likely something both at once – a society.

On the Virtual

This is a virtual artwork in a virtual exhibition in a Virtual Factory. The word 'virtual' does a lot of work, so much that we rarely question what we even mean by 'virtual'. In her book Narrative as Virtual Reality, Marie-Laure Ryan outlines some common understandings of virtual:

- virtual as 'digital': inspired by computer concepts like virtual memory.

- virtual as 'potential': Aristotle argued an acorn has virtus (power) to become a tree.

- virtual as 'fake': Jean Baudrillard's simulacrum, a false virtual double that replaces the real and becomes hyperreal, seeming more real than reality.

For artists, critics and similar occupations prone to exaggeration, Baudrillard's argument is particularly seductive. It warns of a deceptive Other that will replace Us. Reality is under attack! But Ryan is sceptical that her entire sense of reality depends on what this French guy says, and she emphasises a different French guy's ideas – Pierre Lévy's theory of le virtuel:

- virtual as 'pluralistic': a virtual thing functions as many different things.

- virtual as 'non-linear': a virtual thing is not anchored in one space or time.

- virtual as 'inexhaustible': using a virtual thing does not lead to its depletion.

The naked simulated people ('peeps') of We Dwell in Possibility embody le virtuel: they have 2^3 (= 8) different body configurations (thin or thick, breasts or no breasts, penis or vagina) and 6 different skin tones, resulting in 48 possible combinations of body traits; they wrap-around the screen edges in an infinite loop; they can run endlessly without tiring; and sometimes they can even fluidly change their chest or genitals at will.

But I disagree with Baudrillard and agree with Ryan: the virtual does not replace reality. The pandemic has made this clear. Virtual schools, remote offices and Zoom parties have not replaced physical schools, in-person offices, or actual parties – instead, these virtual doubles have just created more school, more work and more people to confront. Peter Sunde, co-founder of the Pirate Bay, famously retorted to lawyers: 'We don't like [saying IRL – In Real Life]. We say AFK – Away From Keyboard. We think that the internet is for real.' If anything, virtual things generate far too much reality, and it's all happening to you right now.

Ryan presents two strategies for this 'virtual as deluge': goal-oriented utilitarians wade through the ocean of shit (aka the internet) to reach their destination, while flâneurs stroll the World Wide Web with minds open toward serendipity and surprise. But more often, we're something in between: we're players.

On Games and Simulation

Gamers enjoy playing with simulations, and that pleasure can teach us a lot about the nature of simulation. The difference between a simulation and its reality is its 'simulation gap', and this lack of correspondence is what makes simulation games interesting. Do not mind the gap! Without this gap, there is nothing to play.

There are 'sims' like SimCity, which seek to be taken semi-seriously as semi-scientific primers to urban planning for educational use in schools. Yet the original SimCity defined crime solely as 'distance from a police station' and nudged its players into libertarian-style low-taxation pro-sprawl strategies. These aren't scientific models – these are political arguments. When designers streamline complex debates like 'what makes a city' into a simplified sim, they inevitably embed their own politics, and the rhetoric of the sim launders these politics as a fact-based algorithmic truth. The sin of the sim is that it minds its gap and tries to hide it.

Then there are 'simulators' like the infallible industrial-grade accuracy of flight simulators (and the game Flight Simulator), which we use to train actual real-life aircraft pilots. But in the last decade, gamers have imbued/tainted this word with a sarcastic tone. For example, the modern simulator game Goat Simulator lets you live as a goat...who also possesses the chaotic power to destroy a small town and ruin countless lives with its 50-foot-long elastic tongue. It totally fails to simulate what being a goat is like – if anything, it simulates how to be a sociopathic asshole – but that absurdity is the point. A truly accurate goat simulation is both impossible and undesirable.

We Dwell in Possibility is obviously not pretending to be a medical-grade ‘sim’ of society, but still seeks to transcend the slapstick irreverence of a ‘simulator’. There's something interesting between these two notions of simulation. Again, we play in the gap.

And in my early prototype, that gap was way too wide. I began by coding some basic cellular automata, a technique popularized by Conway's Game of Life (1970) where cells (or anything, really) live or die based on crowding, but it felt too fiddly with small shapes that changed too quickly. I realised I wasn't interested in population so much as people.

I shifted direction to something more like Claude Shannon's Theseus (1950), a mechanical mouse that ‘learned’ how to navigate a maze by flipping magnetic switches beneath the floor. This is essentially how my simple peep AIs move across the screen: when you drag your cursor (or drag your finger) you're also painting a ‘flow field’ beneath the floor, and the peeps follow that invisible current. The implication is that understanding AI requires us to redefine what we mean by intelligence. Here, the ‘brain’ is distributed across the landscape.

Landscape Architecture and Ecology

Traditionally, Architecture with a capital A has looked down on landscape architecture as a lesser art, neglected beneath the ‘great men’ erecting skyscrapers. But today, millennial climate crisis dread and lack of land ownership have culminated in a profound anxiety about future access to green spaces, clean air and water. Environmentalism has never felt more urgent. We must fix what past generations have done to this planet or everything will die. And part of that process is recognising the world as an ecological system where we all affect each other.

At a glance, this game is about simulating many people moving through a landscape. It mimics the crowd simulation systems used by real-world architects to test building and street circulation. Given our limited resources and time, we had to limit the simulation to a simple ecology.

In We Dwell in Possibility, the ecosystem has four parts:

- 'Peeps' walk around and sometimes pickup nearby 'Plants'.

- 'Plants' (eg large flowers, trees, furniture, statues, kiosks, etc.) can attract Peeps; some Plants modify Peeps by giving them 'Hats'.

- 'Hats' temporarily change Peeps' politics and behaviours.

- 'Players' (ie you) can redirect Peeps and pick up Plants, but cannot affect Hats.

An example of this ecology in action:

- A Churchill Statue 'Plant' looks for nearby Peeps to influence.

- A Peep is attracted to the statue, and gains a Union Jack Hat.

- The Union Jack Hat makes the now-Conservative Peep dislike a nearby Buttplug Obelisk, so the Peep picks it up and wants to get rid of it.

- If the Peep walks off-screen while carrying an object they dislike, they delete that object from the simulation.

- You, the player, can intervene and rescue the Buttplug Obelisk and/or delete the Churchill Statue to prevent future Peeps from gaining Union Jack Hats.

There are dozens of possible Plants and Hats, randomly distributed in each simulation. I won't detail them all. If you're curious, you can just play through a few times and you'll probably encounter most of the combinations.

But my favourite part of this design are the political ramifications of my simple and flawed code architecture. I coded Peeps to wear only one Hat at a time, but then I also had to hack-in handheld objects (cupcakes, coffee, shopping bags) as ‘Hats’ they wear on their hands. But this system design means Peeps must choose: they can either eat a cupcake or they can be a Tory, but they cannot do both. I'm sure there's a very deep political truth in there somewhere, and I've left it as an exercise for the player.

Politics

By now, We Dwell in Possibility's political metaphors are painfully obvious. To use the word 'metaphor' here also strains the meaning of the word. But the design and upkeep of communal public spaces is precisely a political matter – there's no getting around it. Which statues should remain and where? Who is allowed to sell products and services in a park? Who is allowed to sleep in a park? These material questions of governance require political justifications.

As the player, you must indirectly negotiate all these decisions with the Peeps, who bring their own politics and desires into the garden too. For example, there are police in this game. They wear cute little rainbow flags. Should police exist in this garden? Liberal players might try to ‘balance’ a police presence with ‘limited gayness’, queer players might prune all the police entirely and Tory players might engineer a cringe garden consisting solely of police and high street retail, etc. In video games, we call this a ‘sandbox’ – a simulation that is less about ‘winning’ and more about playing with systems that may or may not reflect your values.

I wanted to respond to a lack of politics in crowd simulation art, to push a crowd simulation that has a specific perspective rooted in a specific historical moment. I'm a big fan of KIDS by Michael Frei and Mario von Rickenbach, but personally I can't treat bodies so generically. I also appreciate Ian Cheng's Emissaries series, but dislike its mystification of AI as fantasy novel lore.

The best part of making a sexual-political simulation is the glitches that arise. In my notebook, I've written cryptic phrases: ‘Don't let police ponder cupcakes. Shorten Churchill shadow. Dancing and kissing should be more common. Don't let trees cum. Flowers shouldn't cum at night. Those with hearts should be able to dance.’ I wrote these notes as work task reminders to fix various bugs and problems, but this project's queer politics elevates this to-do list into poetry.

The Title

The title We Dwell in Possibility is from a poem that begins ‘I dwell in Possibility’ (poem #F466A / #J657) by Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), one of the greatest American poets who only became widely-read years after her death. Perhaps the most distinctive aspect of Dickinson's poetry is her punctuation, an ambiguous mark that contemporary readers have interpreted as em dashes – as if she couldn't stop this flood of feeling, interrupting every image and idea:

I dwell in Possibility –

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –

Of Chambers as the Cedars –

Impregnable of eye –

And for an everlasting Roof

The Gambrels of the Sky –

Of Visitors – the fairest –

For Occupation – This –

The spreading wide my narrow Hands

To gather Paradise –

Honestly, it's not Dickinson's best poem, and perhaps it's a little too straightforward, not enough mystery. ‘A fairer House than Prose’ refers to her obvious preference for poetry over prose, followed by some architectural/heavenly imagery. Poetry is a place where she can live with God.

‘To gather Paradise –' is an amazing last line, though. It's as if poetry (‘Paradise’) is more than a place, but also a strange substance, that she is ‘spreading wide [...] to gather’, a virtual contradiction. ‘Possibility’/‘Paradise’ is like this weird virtual thing that we create for ourselves.

But my favourite method is to imagine Dickinson at her most obscene. Imagine someone like Cardi B rapping that last stanza, and it comes off more like she's bragging about how her virtual poetry hands can pleasure the hottest women (‘spreading wide my narrow Hands’... ‘Visitors – the fairest’). Now that's a Possibility we can all dwell in!

So often we think of politics and activism and belief as these terribly dry painful things that we're better off avoiding. Everything is on fire and nothing can be helped, so one must keep their head down and tend to one's own garden. But maybe this game is suggesting there's also some possibility of pleasure out there, and maybe we can all live in it.

Instructions

Click or drag mouse cursor on various things.

Swipe around on your phone, or do nothing and just watch.

At the end, decide whether you've won or lost.

This is a garden. You can’t ‘win’ or ‘lose’ a garden, but maybe you’ll find a way...

Find that utopia.

(10 minute runtime)